Incompatible Timesharing System

| ITS | |

| Type: | Multi-tasking, multi-user, virtual memory |

|---|---|

| Creator: | MIT AI Lab |

| Architecture: | PDP-10 |

| This Version: | 1651 |

| Date Released: | July, 1967 |

The Incompatible Timesharing System (usually ITS) was an early time-sharing operating system; initially for the PDP-6, and later for PDP-10's. It was developed at MIT in the Artificial Intelligence Lab, after Multics was done by Project MAC. It first became operational in July, 1967, after a very short design and implementation period, starting earlier that year.

The earliest versions ran on the PDP-6, using the base and bounds memory management hardware native to that machine. Later versions ran on KA10s which were modified with MIT-designed and built paging hardware (which that generation of PDP-10 CPU did not have). It later ran on the KL10 and KS10 models as well, in both cases running custom microcode that emulated the operation of the MIT paging box.

ITS was one of the first OS's connected to the ARPANET, and it was on an ITS system that the first versions of Emacs, MACLISP, Scheme, and CLU were created, as well as notable games such as Zork.

Contents

Architecture and features

See also ITS Internals Manual

ITS was broadly similar to many other operating systems of its era; each user had a terminal, from which they controlled a tree of processes (called a 'job tree' in ITS; 'job' being the ITS term for a process). The top-level process connected to a terminal was normally a command processor - in ITS' case, the debugger DDT, extended with the usual set of commands: list the files in a directory, etc. Applications (such as editors) each had their own process.

A superior process has complete control of an inferior; it may halt it, read and write in its memory, kill it, etc. A process tree could be detached from its controlling terminal (e.g. if a modem was hung up), for which the ITS term was 'disowned'; the user could reconnect to the system and hook back up to their process tree. Daemons (top-level processes which performed various housekeeping functions) were not attached to terminals.

The earliest versions of the system didn't even support swapping (it is not yet clear if an intermediate version did); paging was added as soon as the custom hardware to support it was done. Pages from other processes could be mapped into a process' address space, as could pages from files. On machines which had front end PDP-11's, their memory could be mapped into processes' address spaces, too.

Processes had full interrupt handling available (with interrupts coming from either hardware, or software, including other processes); the system also supported locks, so that if a process were unexpectedly killed, all locks 'owned' by the process were automatically freed.

I/O was all performed through 'channels', of which each job had up to 16. Channels could connect to a device or a file; they operated in either input or output, and in units of either characters or words (although an entire block of data could be transferred by a single system call, if desired). All the usual operations were provided (open, close, delete, rename, etc). I/O operations could either be synchronous or asynchronous (completion of those notified by interrupts).

ITS had the unusual feature of supporting virtual devices, implemented with demand-created processes into which object code to implement the device was loaded from the file system. This was used, among other things, to make each machine's file system accessible from the others, using their ARPANET connections to carry the data. (This may have been the first example of a 'network file system' in any OS.)

The file system was not very adventurous: it only supported a single level of directories; but it did support symbolic links. (File names had four parts: 'device: directory; fn1 fn2'.) It did have one novel capability (which TENEX also shared); version numbers: when file "FOO >" was opened for reading, if "FOO 22", "FOO 23" and "FOO 24" all existed, 'FOO 24' was opened; opening "FOO <" opened 'FOO 22'. For writing, opening "FOO >" created 'FOO 25'. Unusually, it did not provide any protection; any user could read or write any file in the system.

ITS also supported terminal-type-independent video terminal output; applications would give commands such as 'clear screen', which the system would convert into the appropriate strings for the user's particular terminal.

Instances

See also ITS machine configurations

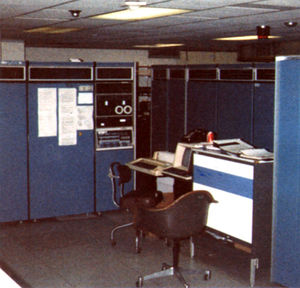

During much of its operational lifetime, ITS ran on only a handful of machines (all at Technology Square):

- The AI Lab PDP-6, serial number 2. (The Dynamic Modeling group also had a PDP-6, not much used.)

- Three KA10s: AI, DM, ML. Their serial numbers were 8, 144, and 198.

- One KL10: MC, serial number 1038.

The AI Lab's PDP-6 and KA10 were joined into a multi-processor system, with shared main memory and devices. Originally, the PDP-6 was the master, where ITS ran, but the two later swapped roles. Due to failing hardware, the PDP-6 was shut down in the late 1970s, and physically removed in the early 1980s. The KA10s followed shortly after, but some were replaced with KS10s. By 1990 all MIT machines were shut down permanently.

In modern times, ITS runs on a KS10 at the Living Computer Museum; it was previously MIT-AI. The museum also has the KL10 MIT-MC in storage. ITS also runs on several software emulators.

Some information on installing & images can be found here.

Milestones

- 1966 - Moby memory acquired and TTY device added four more teletypes; preparing for timesharing?

- 1967 - First version of ITS; ran on PDP-6 — ITS 1.0 3/19/67

- 1968 - Two Data Disc drives added, too small to be useful

- 1969 - Ported to KA10

- 1969 - Second PDP-6 at Dynamic Modeling group

- 1970 - Second KA10 at Dynamic Modeling group

- 1971 - Connected to ARPANET, version ~670

- 1972 - Third KA10 at Mathlab group

- 1975 - Ported to KL10, version 915

- 1978 - PDP-6 support dropped, version 1115

- 1984 - All KA10 machines shut down, first KS10 arrives

- 1985 - Ported to KS10, version 1488, three more KS10s

- 1986 - KS ITS distributed outside MIT (SI, FU, PM, DX)

- 1988 - KL10 machine shut down

- 1990 - All MIT KS10 machines shut down; last MIT version 1644

- 1992 - First run on KS10 software simulator

- 2001 - First simulator available on Internet

- 2010 - First run on an FPGA PDP-10 implementation

- 2017 - First run on KA10 software simulator

Notable contributions

The Artificial Intelligence PDP-6 and PDP-10 were host to many influential programs: TECO (adopted from the one on RLE PDP-1), Logo (coming from BBN), Mac Hack VI, MACLISP, Scheme, EMACS; it was also used to bootstrap the LISP machine hardware and software.

The Dynamic Modeling PDP-10 was used to develop Muddle, MAZE, the first C compiler outside Bell Labs, CLU, and Zork.

The Mathlab PDP-10 was used to develop Macsyma, but was later supplanted by a dedicated Macsyma Consortium KL10.

Early artifacts

The earliest ITS code on record is Gerald Sussman's printed listing of ITS 138 dating from 1967. The title says "ITS 1.0 3/19/67", but it seems the date hasn't been updated. The listing is being processed, with results put here: http://github.com/PDP-6/ITS-138

The next is ITS version 671 from early 1971. It's a complete binary core image, including Salvager and Exec DDT. It runs on Richard Cornwell's KA10 simulator with Systems Concepts DC-10 disks. Also on the same tape is the next earliest source code version, ITS 672.

Stories

ITS, and the hacker culture around it, produced innumerable stories:

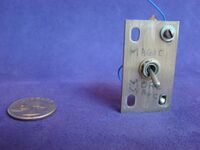

Magic/More magic switch

The AI ITS machine had a mysterious experimental two-position switch attached to the machine at some point, labelled 'Magic' in one position, and 'More magic' in the other. It was only connected to ground, but on several occasions it was observed that throwing the switch crashed the machine!

See also

- PCLSRing

- ITS Internals Manual

- ITS on-disk file system layout

- Versions of important ITS software

- Running ITS (the Incompatible Timesharing System) on the KL-10 - a historical memo

- Systems Concepts DM-10 - Paging box used on several KA10 ITS's

- Systems Concepts DK-10 - Datapoint kludge; AI lab KA10 terminal multiplexor

- Systems Concepts DC-10 - IBM 2314 disk control for the AI lab KA10

- ITS DDT Guide

- MIDAS - the ITS macro assembler, in which most code was written

- Installing ITS on SIMH

- Unix interoperability with PDP-10

- WAITS, another operating system similar in spirit

Further reading

- Steven Levy, Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution, Doubleday, Garden City, 1984 (original edition) - covers much else, but does provide a good non-technical historical overview of the environment and people who produced ITS

External links

- Source code and scripts for building ITS

- ITS documentation - curated

- ITS source - curated

- ITS files - un-curated; raw unsorted dump from CSAIL archives

- ITS HISTRY - list of changes to ITS versions

- An Introduction to ITS for the MACSYMA User - good intro overview to ITS

- INFO;INTRO > - a good starting place for online documentation

- Source code for a very early ITS 1.0 running on a PDP-6

- ITS Status Report - these cover very old versions of the system

- BUG-ITS - archive of email messages (offline now; archived here)

- ITS BUGS - another copy, all in several large archive files

- ITS OBUGS0

- ITS OBUGS1

- ITS OBUGS2

- ITS Topics - ITS page at the Interim Computer Museum DokuWiki

- The Incompatible Timesharing System wiki

- ITS Manual - a new 'Intro to ITS' manual

- ITS on the PiDP 10

- Networking - networking on ITS simulations

- Unix tools for working with ITS files

- ITS Hardware Memo #2 - Specification for the MIT paging box

- The Magic Switch